Some Notes on Deriving Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO)

Bayesian inference approximation commonly relies on variational inference. This technique requires us to maximize evidence lower bound (ELBO). This article discusses three ways to derive ELBO. The outline is arranged as follows. First, we briefly highlight the motivation of variational inference. Subsequently, we provide three ways to derive ELBO. Finally, we end this article by a conclusion.

Background

Performing Bayesian inference requires us to compute posterior distribution. Inference can be thought as a process to quantify unknown variables given the observed variables. Let \(\mathcal{D} = \{x_i\}_{i=1}^{N}\) be a dataset contains \(N\) data points. We can view \(\mathcal{D}\) as the observed variables. Subsequently, we assume there is unobserved parameters \(\theta \in \Theta\) that provide explanations for \(\forall x \in \mathcal{X}\) in general. Inference aims to estimate \(\theta\) given the observations \(\mathcal{D}\). Performing inference under Bayesian theorem provides us a tool to quantify the uncertainty about \(\theta\). Therefore, Bayesian inference is treated as a probabilistic model. The core of Bayesian inference is to evaluate the posterior distribution \(p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})\). This evaluation requires the likelihood \(p(\mathcal{D} \vert \theta)\), prior distribution \(p(\theta)\), and marginal distribution \(p(\mathcal{D})\). The likelihood tells the probability of \(\mathcal{D}\) given a certain \(\theta\). Meanwhile, prior \(p(\theta)\) provides our belief about \(\theta\) before we perform the inference. The third one is marginal distribution \(p(\mathcal{D})\) which represents the probability \(\mathcal{D}\) without the conditioning constraint. By applying Bayes’s theorem, we can write \(p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})\) as:

\begin{equation} \label{eq:posterior-distribution} p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D}) = \frac{p(\mathcal{D}, \theta)}{p(\mathcal{D})} = \frac{p(\mathcal{D} \vert \theta) p(\theta)}{p(\mathcal{D})} \end{equation}

Under the assumption that each data point \(x_i\) is i.i.d., we have \(p(\mathcal{D} \vert \theta) = \prod_{i=1}^{N} \, p(x_i \vert \theta)\). It seems like we are done with the problem. However, computing posterior distribution directly is not feasible.

Posterior distribution has a problem with computation intractability and we need variational inference to solve the issue. We obtain the marginal distribution \(p(\mathcal{D})\) by integrating \(p(\mathcal{D}, \theta)\) over all possible \(\theta\). Formally, we can write \(= \int p(\mathcal{D}, \theta) d\theta = \int p(\mathcal{D} | \theta) p( \theta) d\theta\). Evaluating the distribution is often intractable. Intractablity can have two meanings:

- The marginal distribution \(p(\mathcal{D})\) has no closed-form solution.

- The marginal distribution is computationally intractable (especially when \(x\) is high-dimensional). Look at [Blei, 2016] for more details

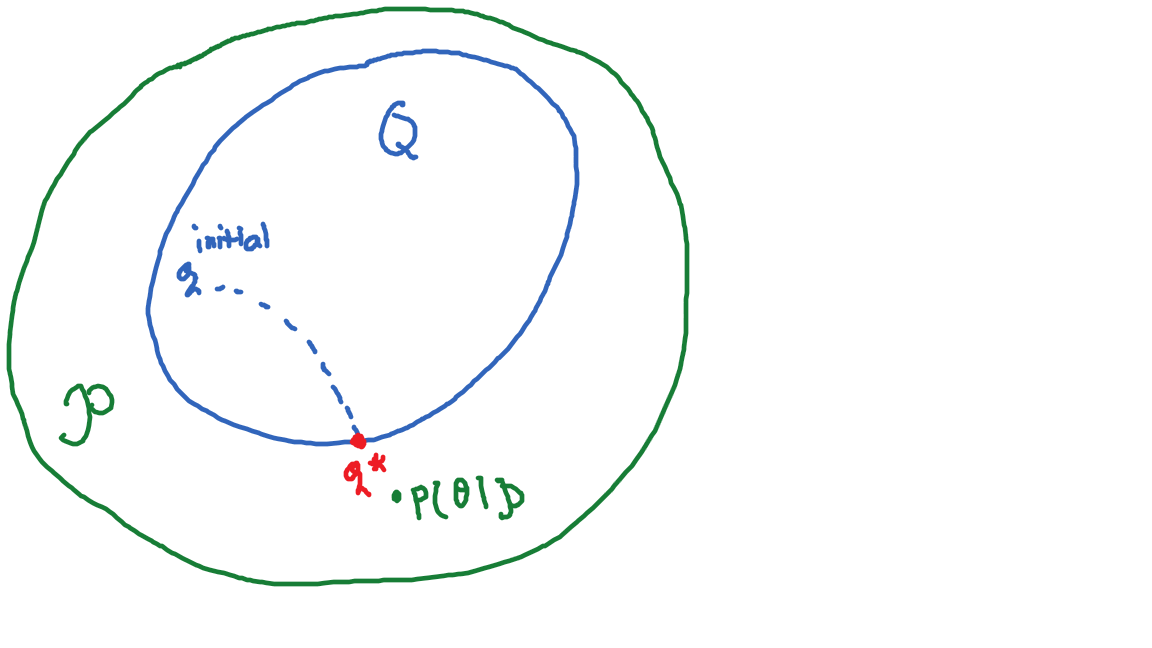

We mitigate the intractability with the help of variational inference. Variational inference approximate the posterior \(p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})\) by using a variational distribution \(q_{\phi} \in \mathcal{Q}\) parameterized by \(\phi\). Commonly, the variational distribution has a simpler form and relatively easy to compute. The goal is to find \(q^* \in \mathcal{Q}\) that is closest to \(p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})\). For now, let’s just assume there is a function \(D[. \| .]\) that is able to measure the closeness between \(q_{\phi}(\theta)\) and \(p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})\). The idea is to choose the parameters \(\phi\) from the parameter space \(\Phi\) that minimizes \(D[q_{\phi}(\theta) \| p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})]\). Mathematically, we can write the objective of variational inference as follows:

\begin{equation} \label{eq:variational-inference} q^* = \underset{\phi \in \Phi}{\text{min}} \, D[q_{\phi}(\theta) | p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})] \end{equation}

Now our inference problem turns into an optimization problem. Figure below gives an illustration of variational inference. We start with an initialized distribution \(q\). Eventually, we obtain \(q^*\) through optimization process. By doing approximation, we trade some accuracy with a more efficient computation. But, how do we define \(D[. \| .]\) ?

Deriving ELBO by Minimizing KL-Divergence

In this section, we introduce KL-divergence as a way to define \(D[. \| .]\). Based on KL-divergence, we derive ELBO, a more practical objective function of variational inference. Given two distributions \(p\) and \(q\), KL function \(KL[. \| .] : \mathcal{P} \times \mathcal{P} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) has the following form: \begin{equation} \label{eq:kl-divergence} KL[p | q] = \mathbb{E}_{p(\theta)}\left[ \log \frac{p(\theta)}{q(\theta)} \right] = \int p(\theta) \log \frac{p(\theta)}{q(\theta)} d\theta \end{equation} Some properties of KL-divergence including:

- KL-divergence is zero iff \(p=q\)

- KL-divergence is not symmetric, that is \(KL[p \| q] \neq KL[q \| p]\)

- KL-divergence satisfies \(KL[. \| .] \geq 0\)

Having a minimum KL-divergence means that we can obtain a tight approximation of \(p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})\). By applying the conditional probability theory and log properties on \(KL[q_{\phi}(\theta) \| p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})]\), we obtain:

\[\begin{eqnarray} KL[q_{\phi}(\theta) \| p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})] &=& \mathbb{E}_{q_{\phi}(\theta)}\left[\log \frac{q_{\phi}(\theta)}{p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})} \right] \nonumber \\ &=& \mathbb{E}_{q_{\phi}(\theta)}\left[ \log \frac{q_{\phi}(\theta)p(\mathcal{D})}{p(\mathcal{D}, \theta)} \right] \nonumber \\ &=& \mathbb{E}_{q_{\phi}(\theta)}[\log p(\mathcal{D})] + \mathbb{E}_{q_{\phi}(\theta)}\left[\log \frac{q_{\phi}(\theta)}{p(\mathcal{D}, \theta)}\right] \nonumber \\ &=& \log p(\mathcal{D}) - \mathbb{E}_{q_{\phi}(\theta)} \left[ \log \frac{p(\mathcal{D}, \theta)}{q_{\phi}(\theta)} \right] \label{eq:elbo-kl} \end{eqnarray}\]From Equation \eqref{eq:elbo-kl}, we can minimize \(KL[q_{\phi}(\theta) \| p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})]\) by maximizing \(\mathcal{L} = \mathbb{E}_{q(\theta)} \left[ \log \frac{p(\mathcal{D}, \theta)}{q(\theta)} \right]\). The later term is called evidence lower bound (ELBO). \(KL[q_{\phi} \| p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})]\) tells us the gap between \(\log p(\mathcal{D})\) and \(\mathcal{L}\). When \(KL[q_{\phi}(\theta) \| p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})] = 0\) then \(\log p(\mathcal{D}) = \mathcal{L}\). Discarding the KL-term from \eqref{eq:elbo-kl} gives us an inequality:

\begin{equation} \log p(\mathcal{D}) \geq \mathbb{E}_{q(\theta)} \left[ \log \frac{p(\mathcal{D}, \theta)}{q(\theta)} \right] \end{equation}

Eventually, our optimization problem turns into ELBO maximization:

\begin{equation} q^* = \underset{\phi \in \Phi}{\text{max}} \, \mathbb{E}_{q(\theta)} \left[ \log \frac{p(\mathcal{D}, \theta)}{q(\theta)} \right] \end{equation}

It turns out that deriving ELBO from KL-divergence is not the only way. In the next two sections, we elaborate different approaches to derive ELBO.

Deriving ELBO by Using Jensen’s Inequality

In this section, we show how to derive ELBO by using the definition of \(\log p(\mathcal{D})\) and Jensen’s inequality. Recall that we can obtain marginal distribution \(p(\mathcal{D})\) by marginalizing the joint distribution \(p(\theta, \mathcal{D})\) over \(\theta\). Now, let us define \(\log p(\mathcal{D})\) by involving the variational distribution \(q_{\phi}(\theta)\).

\[\begin{eqnarray} \log p(\mathcal{D}) &=& \log \int p(\mathcal{D}, \theta) d\theta \nonumber \\ &=& \log \int \frac{p(\mathcal{D}, \theta) q(\theta)}{q(\theta)} d\theta \nonumber \\ &=& \log \mathbb{E}_{q(\theta)} \left[ \frac{p(\mathcal{D}, \theta)}{q(\theta)} \right] \label{eq:convex-elbo} \\ \end{eqnarray}\]In order to derive ELBO, we rely on Jensen’s inequality. In the context of probability theory, Jensen inequality states that:

If \(X\) is a random variable and \(f:X \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is a convex function, then it satisfies \(\mathbb{E}[f(X)] \leq f(\mathbb{E}[X])\).

Now, convince yourself that Equation \eqref{eq:convex-elbo} is a convex function. Therefore, it satisfies:

\begin{equation} \label{eq:elbo-jensen} \log p(\mathcal{D}) \geq \mathbb{E}_{q(\theta)}\left[ \frac{p(\mathcal{D}, \theta)}{q(\theta)} \right] \nonumber \end{equation}

Alternative Derivation

In this section, we derive the last approach to obtain ELBO. This approach is based on the Bayes’s theorem. Observe that we can rearrange Equation \eqref{eq:posterior-distribution} as follows:

\begin{equation} p(\mathcal{D}) = \frac {p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D}) p(\theta)}{p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})} \nonumber \end{equation}

This equation holds for any \(\theta\). Subsequently, let us take the log for both sides:

\begin{equation} \log p(\mathcal{D}) = \log p(\mathcal{D}, \theta) - \log p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D}) \nonumber \end{equation}

Now, let us include the variational distribution \(q_{\phi}\) without affect the equation above:

\[\begin{eqnarray} \log p(\mathcal{D}) &=& \log p(\mathcal{D}, \theta) - \log p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D}) + \log q_{\phi}(\theta) - \log q(\phi)(\theta) \nonumber \\ &=& \log p(\mathcal{D}, \theta) - \log \frac{p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})}{q_{\phi}(\theta)} - \log q_{\phi}(\theta) \nonumber \end{eqnarray}\]Recall that \(\log a \leq a - 1 \leftrightarrow - \log a \geq 1 - a\) for \(a \in \mathbb{R}^{+}\). Using this inequality, we have:

\[\begin{eqnarray} \log p(\mathcal{D}) &=& \log p(\mathcal{D}, \theta) - \log \frac{p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})}{q_{\phi}(\theta)} - \log q_{\phi}(\theta) \nonumber \\ &\geq& \log p(\mathcal{D}, \theta) - \log q_{\phi}(\theta) + 1 - \frac{p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})}{q_{\phi}(\theta)} \nonumber \end{eqnarray}\]Since it is true for all \(\theta\), then it is also true under expectation. Therefore:

\[\begin{eqnarray} \log p(\mathcal{D)} &\geq& \int q_{\phi}(\theta) (\log p(\mathcal{D}, \theta) - \log q_{\phi}(\theta) + 1 - \frac{p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})}{q_{\phi}(\theta)}) d\theta \nonumber \\ &=& \int q_{\phi}(\theta) \log \frac{p(\mathcal{D}, \theta)}{q_{\phi}(\theta)} d\theta + 1 - \int q_{\phi}(\theta) \frac{p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D})}{q_{\phi}(\theta)} d\theta \nonumber \\ &=& \int q_{\phi}(\theta) \log \frac{p(\mathcal{D}, \theta)}{q_{\phi}(\theta)} d\theta + 1 - p(\theta \vert \mathcal{D}) d\theta \nonumber \\ &=& \int q_{\phi}(\theta) \log \frac{p(\mathcal{D}, \theta)}{q_{\phi}(\theta)} d\theta + 1 - 1 \nonumber \\ &=& \mathcal{L} \end{eqnarray}\]Finally, we obtain ELBO without using KL-divergence.

Conclusion

In conclusion, variational inference is introduced to overcome the intractability of computation posterior. In this article we elaborate 3 different ways to derive ELBO. The first approach is based on KL divergence between variational distribution \(q_{\phi}(\theta)\) and posterior \(p(\mathcal{D} \vert \theta)\). The second approach relies on marginalization of joint distribution and Jensen inequality. Finally, we show that ELBO can be derived based on the original Bayes theorem.

References

- Bishop, C. M., & Nasrabadi, N. M. (2006). Pattern recognition and machine learning (Vol. 4, No. 4, p. 738). New York: springer.

- Blei, D. M., Kucukelbir, A., & McAuliffe, J. D. (2017). Variational inference: A review for statisticians. Journal of the American statistical Association, 112(518), 859-877.

- Adams, R. (2020) The ELBO without Jensen, Kullback, or Leibler. Laboratory for Intelligent Probabilistic Systems, Princeton University, Department of Computer Science, https://lips.cs.princeton.edu/the-elbo-without-jensen-or-kl/.